“Religious prescriptionist” are folks who try and tell us what is the TRUE form of their religion, including true doctrines or practices. They tell us what a True Muslim is, what a True Christian is, what a True Hindu is. Heck, this can even happen in non-religious groups: Atheists and Marxists fight among themselves also in this way.

“Religious prescriptionist” are folks who try and tell us what is the TRUE form of their religion, including true doctrines or practices. They tell us what a True Muslim is, what a True Christian is, what a True Hindu is. Heck, this can even happen in non-religious groups: Atheists and Marxists fight among themselves also in this way.

It is not only the fundamentalists that do this, but even the liberals of the religion. These liberals who believe in a more inclusive version of their faith, will try and tell us that such a stance was indeed the real stance of their religious hero: prophets, saviors or saints. You see, they know the truth — just like their fellow fundamentalists. They know how to correctly interpret their sacred, authoritative scriptures. So in a sense, they are doing the same thing as their fundamentalist

It is very common human trait to choose a group’s identity banner and then work to get others to agree with your particular view on that group.

A Buddhist Example:

For instance: Some Buddhists believe in “Other-Help” (tariki, in Japanese). They believe that meditation is too hard a path but that we are now in a dispensation where faith is the only true path of Buddhism. They believe that if their heart felt prayers (chanting) to Amida Buddha are sufficiently they can go to Buddhist heaven. Sound familiar?

Sure, they may call themselves “Buddhist”, but their commonality with many Christians is uncanny. And Buddhists who say that these Buddhist aren’t really Buddhists are being “prescriptivists”.

A Muslim Example

A Muslim declares that true Islam is peaceful and not condemning of other faiths. Sure, their flavor of Islam may be so, but many versions of Islam disagree. Further, that believer and the others rely on the same idea of using correct interpretation of scripture as their source of authority.

Summary of main points:

- Prescriptivists exist in all faiths

- No matter how loud the prescriptivists yell, all faiths (all groups) will continue to have a varieties of followers who hold contradictory beliefs, practices and preferences

- Prescriptivists teach us a great deal about “groupism”

- Our understanding of groups (both faith and non-faith groups) will improve if we understand the prescriptionists and prescriptivism

- Understanding this comparative religion trait helps us understand groups which helps us better understand our minds and our societies.

- Religious folks need to stop pretending as if their religion is homogenous or as if they know the one true teaching.

When someone tells me what the only “true” view/practice is, I know that’s my queue to exit.

@ Adam :

Indeed !

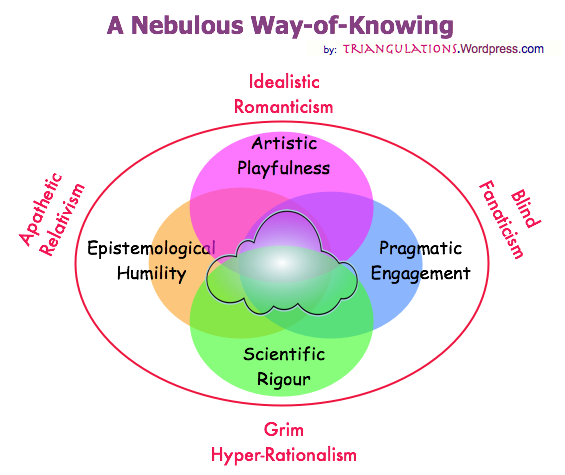

Of course I want folks to be sure to understand that I am not calling for relativism (ie., “all beliefs or practices are equally good”) because here I am talking about “group labels”, not “valuable practices or beliefs”. I am discussing the whole “groupism” phenomena — not how we wrestle with what is valuable.

You and I have the same reaction it seems!

If someone who claimed to be libertarian wanted to outlaw homosexuality, would it be prescriptionist to say that he’s not?

Hmmmm ….

I guess it depends how he defines libertarian. Libertarians define themselves in all sorts of ways — even if you and I would not agree with them.

Dog-gone-it, why won’t the just let me write the acceptable definitions! 🙂 (oops, forgot, you don’t like those)

So, is there a post coming up with the title “Religious Descriptionists”?

I’m really disappointed to hear about the Other-Help Buddhists. Not surprised, but disappointed.

I especially like your points about how this is not just a religious phenomenon. There is a ton of baggage to unpack around how we think things should be compared to how things are.

@ Andrew :

Perfect. Thanks for understanding — wheeew. Yes, “descriptionist” is the opposite. “Prescriptivists” are also “Normativists” (if I understand the usage of that terms. I think we are either prescribing/normalizing or describing. (OK, I kind of just said that and am not sure if it is true, but there you go). I think we should be clear on which we are doing. Both are fine, but being aware of one’s activity is important. AND, understanding the artificial nature of prescription as a political move is important.

@ Petteri :

Yeah, ugly world, but that would be true. Many years ago I was the chairperson of the Libertarian committee in my county in another state. I was surprised by all the variety of libertarians that exist — all of them claiming to be the “right” kind, of course. That was “enlightening”. Lots of stories there, but not posted yet.

If a given “libertarian” defines “libertarian” a certain way that is bizarre to others but over time gets enough to agree, then that “nuance” or “definition” of the word may enter dictionaries. Same with Marxists, Artists, and many more. Of course the more concrete a group’s work is, the less flexible the terms seem — like “woodworker”. Language is fluid like that. Groups and politics shape language and ideas. Nothing is stable.

@ Petteri :

Wow, I just searched for the term “religion prescriptivist” and didn’t find it accept in my post. It seems I coined a new phrase! You watch, this will go viral and a new term will enter English — then through you, a year later, it will be in Finnish dictionaries! 😀

Sabio; I actually own the word “religious prescriptivist”, and it doesn’t mean what you say at all.

🙂

Very good, Sabio!

Now, suppose a self-declared libertarian would announce that he believes that the best way to maximize liberty in a society is to have a strongly redistributive system of taxation backed by a strong state, so the rich minority wouldn’t use their economic power to deprive the poor majority of their liberty.

(1) Would it be prescriptionist for other libertarians to resist his attempt to get them to accept this as a libertarian position?

(2) Suppose he got a lot of media attention, and convinced a few people to join him. How much attention and how many people would it take before his position would have to be accepted as libertarian?

@ JS

I thought the government stepped in an broke-up your monopoly on “religious prescriptivism” or was it that they suspended your prescription-writing authority? 😀

@ Petteri

Very good, I am glad you are following along.

Yes, the word could be turned inside out and resisting it, would be a prescriptionist move.

I think we have examples of words like that changing — take “liberal”, for instance.

And remember, as my note to Andrew said, you are either describing or prescribing. They both have their roles. It is awareness that is key. And also, as you illustrate for me, it is important to understand how political words are — especially the more abstract they get. Take “Freedom” or “Liberty”, for instance. Or take “Enlightenment”.

@ Petteri :

Imagine that you have Buddhist writer who is saying that “Real Buddhism” should not involve chanting nor belief in Rebirth and that those who practice these are not practicing Buddhism but are deluded. Now imagine 2 other writers or preachers pushing for the opposite or competing views. I would say that they are practicing (at those moments) as “religious prescriptionists”. Feels like an appropriate phrase for me. Do you have a better phrase or suggestion?

Now, if someone said, “I don’t see a need to chant or believe in rebirth, but their are all sorts of Buddhism and this is my way.” Then I would not call that prescriptivism.

Yes, the word could be turned inside out and resisting it, would be a prescriptionist move.

In that case, I submit that your concept of ‘prescriptionism’ is a dead end, since it appears to encompass any attempt to arrive at an even provisionally stable definition of a concept.

There are ways out of this dead end.

Consider the following propositions:

P1. “I R baboon!” is not grammatical English.

P2. Redistribution through progressive taxation is not a libertarian notion.

P3. Human sacrifice is not Christian.

My suggestions would be

(1) to dump the term ‘prescriptionist’ in favor of the better-established term ‘normative,’ and

(2) to attempt to figure out why propositions P1, P2, and P3 above are not necessarily normative, but also valid within a descriptive system, even if you’re able to find some English-speakers using the phrase, some libertarians espousing that notion, or some Christians engaging in that practice.

I would suggest study of methodological nominalism and the emergence of descriptive approaches to grammar as methods for (2).

I believe that should you do so, you would find your ability to understand and speak of systems such as grammars, political philosophies, or religions greatly enhanced, without having to fall into sterile dogmatism.

And that’s all I have time for today.

@ Petteri :

I think you made a helpful suggestion: Often to clarify a disagreement, it can be a wise (as you have done) to move the dialogue to discuss another situation where neither party is highly invested, and yet that situation contains the same principle as the loaded situation. Since it is the situation/phenomena/logic we are discussing.

Here, talking about the classic trio of religion, politics and/or sex can be very loaded depending on the investments of the two folks dialoguing. For us, politics and religion may be clouding the issue. So I think your move to discussing a similar principle which happens in language may be very helpful.

Your example of P1 [“I R baboon!” is not grammatical English] may prove such a wise move.

There exists many dialects of English. Many have internal consistency in grammar and yet deemed “ungrammatical” by the other but each calling itself English. But if pushed, they may each willingly add an adjective to “English” to illustrate the differences: British English, Jamaican English, Indian English …

But a Language Prescriptionist — as the French are infamous for being, would try to avoid change and variety by moving to make an “orthodox” French. When I taught English in Japan, my fellow University instructors were divided between the “normative” Folks (“the prescriptivists”) and those that felt language was fluid. The fluid folks were more willing to acknowledge the political nature of language and would teach varieties of English if appropriate and help students realize what forms of English were accepted by what political/social groups. The Normative folks (I am not attached to the wording — though I think mine is still very useful), did not want to budge and wanted to say that “Sure, my English has more power, but it is also the true English.” Yeah, right.

So I guess I disagree with you. I DO see P2 as normative. Sure, it is descriptive if everyone agrees with a given set of rules. But the whole point of my post is that not everyone agrees with the same set of rules.

Hopefully we are trying to understand each other. Here is a post where I outright declare myself a “Nominalist” when discussing “abstract objects”. I used that post to try to facilitate these sort of conversations. I am certainly not an essentialist. (as many posts of mine have illustrated) So I am not sure if you want me to just switch terms or if in some way you feel I am highly mistaken and that my post does not illustrate any valuable issue.

As for your last paragraph, I am glad you feel further education would improve my ability to get religion, politics and grammars right. I certainly agree that further education would certainly make my arguments more coherent, but not necessarily more “right”. But let’s tackle this language example for now instead of discussing my global deficiencies.

That is all I have time for today. I am busy on my next post about hemorrhoids — seriously!

Ooops, I lied. Hemorrhoids are going to have to wait:

I just tried to have a discussion with my kids about animal classification yesterday and we I tried to introduce them to nominalism but it was a tough discussion. For I think kids are natural-born essentialists (as Bruce Hood discusses in his book “SuperSense”). Here is a link to a 1993 article discussing this exact conversation (albeit in simpler terms) that I had yesterday with my kids about mammals. In case you wonder if I get this stuff. Or am I missing something?

Is there an essential Buddhism or essential Christianity? — Prescriptivists think so (ooops, Essentialists think so).

I posted on Karen Armstrong about this a couple of days ago. It seems she is a religious prescriptivist about *other* religions. Muslims who believe in militant jihad are not ‘true’ muslims, they are even ‘abusing’ their religion.

I am definitely of the opinion that this kind of description (as well as “atheist”, “humanist”, “libertarian”) are purely subjective labels that one may want to take on from time to time. Okay their meaning clusters around particular loci, but I have no problem with Fred Phelps being a Christian as well as my non-practising liberal anglican mother.

At one level there is one Christianity, because there is one label. But if you look closely there are many, and if you look really closely, each person means a different thing by the word.

@ Ian

I agree ! Well said. I am not sure what Petteri is after.

I hope Petteri, above, visits your site. He, like you, has a strong intellect and perhaps you would find it fun to wrestle with ideas. I recommended your site to him before, I think.

You appear to understand the problems related to normative systems well, and I fully agree with you about them.

However, it also appears that you don’t fully grasp how descriptive systems work, at least when applied to complex, fuzzy, fluid, and evolving constructs like grammars, religions, or (political) philosophies.

Therefore, you’re still floundering in a trap: we’ve established that you haven’t found a way to get rid of normative systems without altogether discarding the notion of workable, stable definitions. Unfortunately, without such definitions, it’s not possible to speak meaningfully about anything at all!

This is a fundamental flaw, so fundamental, in fact, that it makes your argument not merely invalid, but entirely meaningless.

It wouldn’t take a very large modification to make it meaningful again. I’ve tried to show you the trap, and pointed you towards paths that lead out of it. Since you requested that I keep my comments short and to the point, I can’t help you any further. Good luck!

I think the best (least loaded) example of the prescriptive/descriptive distinction Sabio is making would be the contrast between how L’Académie française determines word meanings and how Google determines word meanings.

On the one extreme, L’Académie française creates the official dictionary of French word meanings. This dictionary is far less “descriptive”, and far more resistant to normative changes than are dictionaries like OED or Webster’s. It’s basically written by the most elite intellectuals in Paris. Additionally, it is far more strictly “enforced” on the population. The French demand far greater homogeneity in the language across all speakers across the world, in contrast to other languages.

On the other extreme, we have search engines like Google, who infer word meanings from context and statistical patterns of use, drawn from a corpus of billions of Web pages. When a new word usage or phrase comes into being, Google picks it up with no human intervention.

This distinction is roughly equivalent to the distinction between “knowledge representation” and “machine learning” in AI research. The KR people would prescribe huge taxonomies and ontologies, designed by experts, and try to jam all of knowledge into those. Machine learning, on the other hand, just looks at what’s out there and tries to make sense of it.

@ JR :

Thanks — another reader understands.

@ Petteri :

Dude, I think I understand the balance between the limits of and benefits of normative vs descriptive uses of language. You might want to attack another windmill.

Touchy touchy!

Sorry, Sabio, but clearly you don’t, since your understanding leaves you totally open to a simple rhetorical trick like I described at 1:34.

You got pretty close to the solution with your reply at 4:15. However, you went back into the woods in 4:40.

I’ll give you a few more hints:

(1) What would happen if you considered the questions of identity and ‘practice’/’structure’/’doctrine’ as interrelated but distinct questions?

(2) What would happen if you introduced a historical perspective into your models of religions, philosophies, and languages?

Here are three more statements:

“It is possible for an English-speaker to speak nongrammatical English.”

“It is possible for a Libertarian to hold a non-libertarian political position.”

“It is possible for a Christian to hold a non-Christian belief.”

Your homework is to explain how they can be true, even within a descriptive/nominalist framework. If you can’t, you don’t really understand methodological nominalism.

(Don’t sweat it too much, though: if you fail, you can always apply for tenure in France.)

Care to explain why you think your three statements might confound any nominalist, or in fact anyone? Seems like they’re actually all pretty simple and demonstrable claims to me.

You seem to be pretending that a pretty standard view in the philosophy of language is somehow untenable. Obviously you seem to think that your ‘rhetorical trick’ in 1:34 was somehow tricksy. But it is a pretty standard idea, and not trivially refutable.

Time to shake of the shackles of Platonic reasoning.

@Ian, of course they’re very simple and demonstrable, and the rhetorical trick was extremely common and simple! That’s the point!

However, they appear to confound Sabio.

Earlier, in he stated that ‘”I R baboon!” is not grammatical English’ is necessarily a prescriptionist statement, even though it obviously isn’t (in 11:39).

Those three simple and easily demonstrable claims are just the same claims I made earlier, made a little bit easier. If he can get through those, he ought to be able to demonstrate the earlier, more specific claims too, or at least show how they could be demonstrable—and get out of the uncomfortable corner in which he found himself with the bit of dialog about the socialist co-opting libertarianism.

That, however, will produce a new problem: he will no longer be able to claim that any statement of the form ‘X is not Y’ where X is a belief, policy, or practice and Y is a religion or political philosophy is ‘prescriptionist’—a position he’s using as a ‘win any debate free’ card here. That’s a cheap and simple rhetorical trick too, just as cheap as the one from 1:34.

As I said, he’s close, but apparently not quite there yet. He understands the problems with normative/essentialist systems very well, which is very good, but he doesn’t appear to have discovered a solution that doesn’t devolve into ‘all discourses are equally valid’ pap.

It could be I’m mistaken, of course. If so, it ought to be very easy for him to correct that misapprehension. Why do you think he hasn’t done that yet, and is still arguing against some silly essentialist strawman? Come to think of it, why are you?

(For the record, I am not an essentialist, and I am strongly opposed to normative grammars.)

PS—what I’m talking about is this (Sabio at 4:40):

“Yes, the word could be turned inside out and resisting it, would be a prescriptionist move.”

That’s his response to my imaginary socialist attempting to co-opt libertarianism. If his definition of ‘prescriptionism’ goes as far as that, he has painted himself into the postmodernist corner.

Good comments.

One problem with prescriptivism is that people will generally interpret any standard to suit themselves. This is especially a problem if they’re ignorant of what those standards actually entail.

Take your example of “Other-Help” Buddhists (from your description, I’m assuming you mean Shin Buddhists), According to its founder’s major writings, it’s metaphorical: “Amida Buddha” is really Buddha-nature, the “Pure Land” is really a pure state of mind, etc. However, because some (who are ignorant of it, deliberately or otherwise) want to believe in a literal magical being presiding over a magical land who saves them, it gets turned into what you describe.

In the hands of people like this, prescriptivism just becomes a club to beat others into conformity, a way to arbitrarily claim “I’m better than you!”

@ David :

I agree, prescriptivism can become a club to beat people. However, when a group agrees to work on a common agreed prescription for the group — by consensus so as to get a common desired goal –then we have another possibly healthy use of prescriptionism. But that is not what either you nor I are talking about — we are talking about declaring the meaning of abstract words to have your and only your definition.

BTW, can we assume that you are a Shin Buddhist?

Here is the wiki article for unfamiliar readers.

I must say, I am not familiar with all the variety of believers within Shin Buddhism and your comment here have helped me see some variety. I look forward to learning more from your site (may I post it?). When living in Japan, I only new a few Shin believers personally, and they all believed in a literal magical being over a magical land. What percent of Shin believers are literalist? I’d imagine a good analysis would need to separate Japanese, Chinese, and “Westerners” to help clarify.

@Sabio

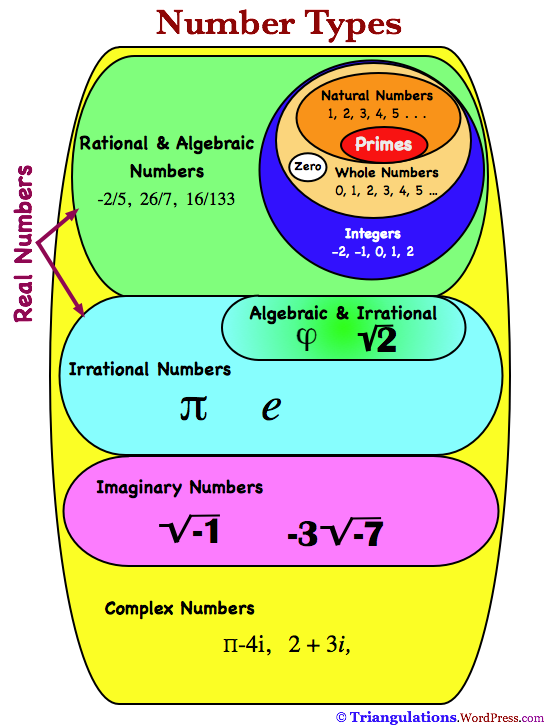

Regarding declaring the definitions of words: Understood. Such stringent definitions only really make sense for abstract facts. In, say, mathematics, if someone says two plus two is four, how many people can seriously argue about different meanings for four and still accomplish anything?

Regarding your other questions that I can answer: Yes, I am a Shin Buddhist, I’m definitely not a literalist, either in it or in general. I don’t yet have a site. (You should probably also mentally prefix everything I say on the subject with “if I understand this correctly”.)

@ David

Ah, I thought maybe you were the author of this new Shin site I found. It seems the author of that site also holds a view of Shin that I am not familiar with. So much to learn. I love when folks broaden my understanding. Hope you visit again.

well no true Christian would post here anyway. this is an atheist’s site and no true Scotsma… i mean Christian would talk openly with you, only try to convert you.

wait a sec…

“Prescriptivists exist in all faiths” i agree they do. i would expand that and say that they may exist in all social ideologies. i think i’m seeing it emerge in Atheist circles but want your thoughts on it as well, because i don’t want to paint a group with a broad brush.

i think that Dawkins, Hitchens and the other two are attempting a “Nicene moment.” There seems to be a laying down the hard-line complete with the ideology, insider terminology, and other such like stuff that go along with a “tribal mindset.” this thinking states that if you’re religious, you’re irrational and of the conservative variety (despite what your objections, and if you object, it’s your irrationality and not my ignorance that is the problem). if you’re an atheist who believes religion has a place in society (aside from small minded fairy tales), then you’re an accommodationist. thus the “No True Atheist Likes Religion” claim.

i could be way off… what do you think?

Pingback: How to deal with real life as a Buddhist. « Alternative Health Answers